Veda Studies and Knowledge

(NameENG)

Notes

READ MORE

Notes

READ MORE

English pronunciation : véda / Vētā / Vētam / Vēdham āyvukaḷ / ñāṉam Vaḷarcci Peṟa / Rikvēdaṁ / Rik vētam / Yajūr vētam / Sāma vētam / Atarvaṉa vētam /

Sanskrit संस्कृतम् : वेद /

Tamil தமிழ் : வேதா / வேதம் ஆய்வுகள் / ஞானம் வளர்ச்சி பெற / ரிக் வேதம் / யஜூர் வேதம் / சாம வேதம் / அதர்வன வேதம்

Bahasa Melayu : Rigvéda / Yajurveda / Sāmavéda / Atharvavéda /

Malayalam : not_available /

Telugu : రుగ్వేదం ( Rugvēdaṁ ) / యజుర్వేదం ( Yajurvēdaṁ) / సామవేదం ( Sāmavēdaṁ ) / అధర్వ వేదం ( Adharva vēdaṁ ) /

Français : not_available

Introduction

The Védas ( Sanskrit : वेद véda, "knowledge" ) are a large body of texts originating in ancient India. Composed in Védic Sanskrit, the texts constitute the oldest layer of Sanskrit literature and the oldest scriptures of Hinduism.

The class of "Védic texts" is aggregated around the 4 canonical Saṃhitās or Védas proper ( turĩya ), of which 3 ( traya ) are related to the performance of yajna ( sacrifice ) in historical ( Iron Age ) Védic religion :

The Rigvéda manuscripts have been selected for inscription in UNESCO's "Memory of the World" Register 2007.

According to Hindu tradition, the Védas are apauruṣeya "not of human agency", are supposed to have been directly revealed, and thus are called Śruti ( "what is heard" ). The 4 Saṃhitās are metrical ( with the exception of prose commentary interspersed in the Black Yajurveda ). The term Saṃhitā literally means "composition, compilation". The individual verses contained in these compilations are known as mantras. Some selected Védic mantras are still recited at prayers, religious functions and other auspicious occasions in contemporary Hinduism.

The various Indian philosophies and sects have taken differing positions on the Védas. Schools of Indian philosophy which cite the Védas as their scriptural authority are classified as "orthodox" ( Āstika ). Other traditions, notably Buddhism and Jainism, which did not regard the Védas as authorities are referred to by traditional Hindu texts as "heterodox" or "non-orthodox" ( Nāstika ) schools. In addition to Buddhism and Jainism, Sikhism and Brāhmoism, many non-Brāhmiṇ Hindus in South India do not accept the authority of the Védas. Certain South Indian Brāhmiṇ communities such as Iyengars consider the Tamil Divya Prabandham or writing of the Alvar saints as equivalent to the Védas. In most Iyengar temples in South India the Divya Prabandham is recited daily along with Védic Hymns.

ETYMOLOGY AND USAGE

The Sanskrit word véda "knowledge, wisdom" is derived from the root vid- "to know". This is reconstructed as being derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *u̯eid-, meaning "see" or "know". As a noun, the word appears only in a single instance in the Rigvéda, in RV 8.19.5, translated by Griffith as "ritual lore" :

yáḥ samídhā yá âhutī / yó védena dadâŚa márto agnáye / yó námasā svadhvaráḥ

"The mortal who hath ministered to Agni with oblation, fuel, ritual lore, and reverence, skilled in sacrifice."

The noun is from Proto-Indo-European *u̯eidos, cognate to Greek (ϝ)εἶδος "aspect", "form" . Not to be confused is the homonymous 1st and 3rd person singular perfect tense véda, cognate to Greek (ϝ)οἶδα (w)oida "I know". Root cognates are Greek ἰδέα, English wit, etc., Latin video "I see", etc.

In English, the term véda is often used loosely to refer to the Saṃhitās ( collection of mantras, or chants ) of the four canonical Védas ( Rigvéda, Yajurveda, Sāmavéda and Atharvavéda ).

The Sanskrit term véda as a common noun means "knowledge", but can also be used to refer to fields of study unrelated to liturgy or ritual, e.g. in agada-véda "medical science", sasya-véda "science of agriculture" or sarpa-véda "science of snakes" ( already found in the early Upanishad or Upaniṣads ); durvéda means "with evil knowledge, ignorant".

CHRONOLOGY

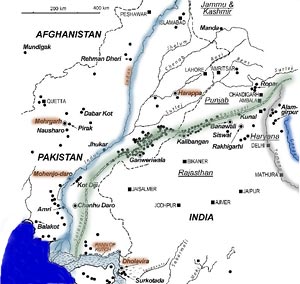

The Védas are among the oldest sacred texts. The Saṃhitās date to roughly 1500–1000 BCE, and the "circum-Védic" texts, as well as the redaction of the Saṃhitās, date to c. 1000-500 BCE, resulting in a Védic period, spanning the mid 2nd to mid 1st millennium BCE, or the Late Bronze Age and the Iron Age. The Védic period reaches its peak only after the composition of the mantra texts, with the establishment of the various shakhas all over Northern India which annotated the mantra Saṃhitās with Brāhmaṃā discussions of their meaning, and reaches its end in the age of Buddha and Panini and the rise of the Mahājanapadas ( archaeologically, Northern Black Polished Ware ). Michael Witzel gives a time span of c. 1500 BCE to c. 500-400 BCE. Witzel makes special reference to the Near Eastern Mitanni material of the 14th c. BCE the only epigraphic record of Indo-Aryan contemporary to the Rigvédic period. He gives 150 BCE ( Pātañjali ) as a terminus ante quem for all Védic Sanskrit literature, and 1200 BCE ( the early Iron Age ) as terminus post quem for the Atharvavéda.

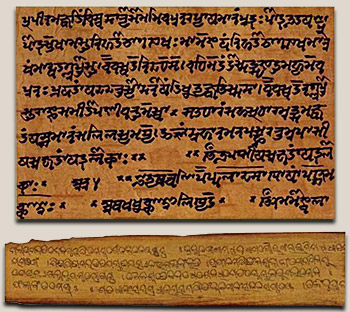

Transmission of texts in the Védic period was by oral tradition alone, preserved with precision with the help of elaborate mnemonic techniques. A literary tradition set in only in post-Védic times, after the rise of Buddhism in the Maurya period, perhaps earliest in the Kanva recension of the Yajurveda about the 1st century BCE; however oral tradition predominated until c. 1000 CE.

Due to the ephemeral nature of the manuscript material ( birch bark or palm leaves ), surviving manuscripts rarely surpass an age of a few hundred years. The Benares Sanskrit University has a Rigvéda manuscript of the mid-14th century; however, there are a number of older véda manuscripts in Nepal belonging to the Vajasaneyi tradition that are dated from the 11th century onwards.

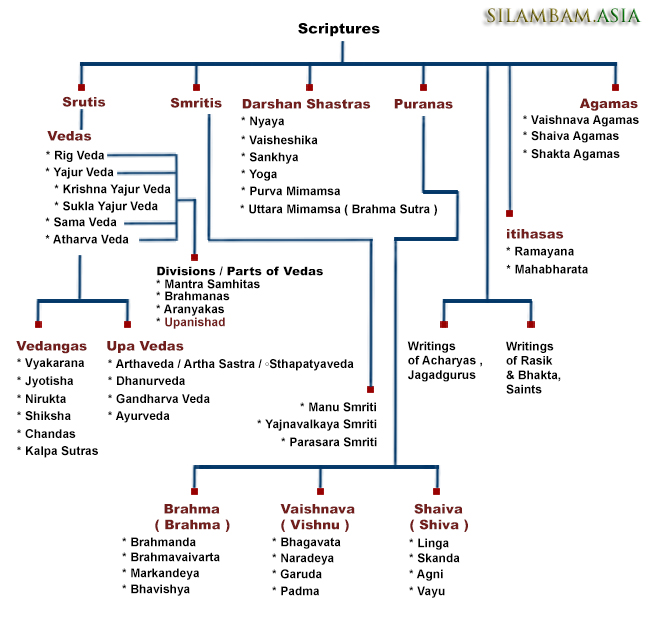

CATEGORIES OF VEDIC TEXTS

The term "Védic texts" is used in two distinct meanings :

1. Texts composed in Védic Sanskrit during the Védic period ( Iron Age India )

2. Any text considered as "connected to the Védas" or a "corollary of the Védas"

VEDIC SANSKRIT CORPUS

The corpus of Védic Sanskrit texts includes :

The Shrauta (Śrauta)Sũtras, regarded as belonging to the smriti, are late Védic in language and content, thus forming part of the Védic Sanskrit corpus. The composition of the Shrauta (Śrauta) and GṛhyaSũtras ( ca. 6th century BC ) marks the end of the Védic period , and at the same time the beginning of the flourishing of the "circum-Védic" scholarship of Védāṅga, introducing the early flowering of classical Sanskrit literature in the Mauryan and Gupta periods.

While production of Brāhmaṇās and Āraṇyakas ceases with the end of the Védic period, there is a large number of Upanishad or Upaniṣads composed after the end of the Védic period. While most of the ten Mukhya Upanishad or Upaniṣads can be considered to date to the Védic or Mahājanapada period, most of the 108 Upanishad or Upaniṣads of the full Muktika canon date to the Common Era.

The Brāhmaṇās, Āraṇyakas, and Upanishad or Upaniṣads often interpret the polytheistic and ritualistic Saṃhitās in philosophical and metaphorical ways to explore abstract concepts such as the Absolute ( Brāhmaṇ ), and the soul or the self ( Atman ), introducing Védāṅta philosophy, one of the major trends of later Hinduism.

The Védic Sanskrit corpus is the scope of A Védic Word Concordance ( Vaidika-Padānukrama-Koṣa ) prepared from 1930 under Vishva Bandhu, and published in five volumes in 1935-1965. Its scope extends to about 400 texts, including the entire Védic Sanskrit corpus besides some "sub-Védic" texts.

A revised edition, extending to about 1800 pages, was published in 1973-1976.

SHRUTI LITERATURE

The texts considered "Védic" in the sense of "corollaries of the Védas" is less clearly defined, and may include numerous post-Védic texts such as Upanishad or Upaniṣads or Sũtra literature. These texts are by many Hindu sects considered to be shruti ( Sanskrit : Śruti; "the heard" ), divinely revealed like the Védas themselves. Texts not considered to be shruti are known as smriti ( Sanskrit : smṛti; "the remembered" ), of human origin. This indigenous system of categorization was adopted by Max Müller and, while it is subject to some debate, it is still widely used. As Axel Michaels explains :

These classifications are often not tenable for linguistic and formal reasons: There is not only one collection at any one time, but rather several handed down in separate Védic schools; Upaniṣads ... are sometimes not to be distinguished from Āraṇyakas...; Brāhmaṇās contain older strata of language attributed to the Saṃhitās; there are various dialects and locally prominent traditions of the Védic schools. Nevertheless, it is advisable to stick to the division adopted by Max Müller because it follows the Indian tradition, conveys the historical sequence fairly accurately, and underlies the current editions, translations, and monographs on Védic literature."

The Upanishad or Upaniṣads are largely philosophical works in dialog form. They discuss questions of nature philosophy and the fate of the soul, and contain some mystic and spiritual interpretations of the Védas. For long, they have been regarded as their putative end and essence, and are thus known as Vedānta ( "the end of the Védas" ). Taken together, they are the basis of the Védāṅta school.

Śruti (Devanagari श्रुति, "what is heard") is a canon of Hindu sacred texts. They do not date to a particular period, but rather stretch across the entire history of Hinduism, beginning with the some of the earliest known Hindu texts, spanning into the modern period with the Upanishads.

Śruti has no author; rather, it is divine recording of the "cosmic sounds of truth", heard by rishi. They are timeless teachings transmitted to rishis, or seers, directly by God thousands of years ago. Sruti is thus said to be apaurusheya, "impersonal," or rather "suprahuman."

Sruti consists essentially of the Vedas and the agama, preserved initially through oral tradition and eventually written down in Sanskrit. Among the many sacred books of the Hindus, these two bodies of knowledge are held in the highest esteem. For countless centuries shruti has been the basis of philosophical discussion, study and commentary, and this attention has given rise to countless schools of thought. It is also the subject of deep study and meditation, to realize the wisdom of the ancients within oneself.

Most mantras are drawn from sruti, used for rites of worship, both public and domestic, as well as personal prayer and japa. It is a remarkable tribute to Hindu culture that so much of sruti was preserved for thousands of years without alteration by means of oral instruction from guru to shishya, generation after generation. In the Veda tradition this was accomplished by requiring the student to learn each verse in eleven different ways, including backwards. Traditionally sruti is not read, but chanted according to extremely precise rules of grammar, pitch, intonation and rhythm. This brings forth its greatest power. In the sacred language of shruti, word and meaning are so closely aligned that hearing these holy scriptures properly chanted is magical in its effect upon the soul of the listener.

SMRITI

smriti: (Sanskrit) "That which is remembered; the tradition."

What is remembered; unwritten teachings handed down by word of mouth, distinguished from srutis or teachings handed down in traditional writings.

Hinduism's nonrevealed, secondary but deeply revered scriptures, derived from man's insight and experience. Smriti speaks of secular matters - science, law, history, agriculture, etc. - as well as spiritual lore, ranging from day-to-day rules and regulations to superconscious outpourings.

The smritis were a system of oral teaching, passing from one generation of recipients to the succeeding generation, as was the case with the Brahmanical books before they were imbodied in manuscript. The Smartava-Brahmanas are, for this reason, considered by many to be esoterically superior to the Srauta-Brahmanas. In its widest application, the smritis include the Vedangas, the Sutras, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the Puranas, the Dharma-sastras, especially the works of Manu, Yajnavalkya, and other inspired lawgivers, and the ethical writing or Niti-sastras; whereas the typical example of the sruti are the Vedas themselves considered as revelations.

The term smriti refers to a specific collection of ancient Sanskritic texts as follows: the six or more Vedangas, the four Upavedas, the two Itihasas, and the 18 main Puranas. Among the vedanga, the Kalpa Vedanga defines codes of ritual in the Shrauta and Shulba Shastras, and domestic-civil laws in the Grihya and Dharma Shastras. Also included as classical smriti are the founding sutras of six ancient philosophies called shad darsanas (Sankhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Mimamsa and Vedanta).

In a general sense, smriti may refer to any text other than shruti (revealed scripture) that is revered as scripture within a particular sect. From the vast body of sacred literature, shastra, each sect and school claims its own preferred texts as secondary scripture, e.g., the Ramayana of Vaishnavism and Smartism, or the Tirumurai of Saiva Siddhanta. Thus, the selection of smriti varies widely from one sect and lineage to another.

VEDIC SCHOOLS OR RECENSIONS

Study of the extensive body of Védic texts has been organized into a number of different schools or branches ( Sanskrit Śākhā, literally "branch" or "limb" ) each of which specialized in learning certain texts. Multiple recensions are known for each of the Védas, and each Védic text may have a number of schools associated with it. Elaborate methods for preserving the text were based on memorizing by heart instead of writing. Specific techniques for parsing and reciting the texts were used to assist in the memorization process.

Prodigous energy was expended by ancient Indian culture in ensuring that these texts were transmitted from generation to generation with inordinate fidelity. For example, memorization of the sacred Védas included up to eleven forms of recitation of the same text. The texts were subsequently "proof-read" by comparing the different recited versions. Forms of recitation included the jaṭā-pāṭha ( literally "mesh recitation" ) in which every two adjacent words in the text were first recited in their original order, then repeated in the reverse order, and finally repeated again in the original order.

That these methods have been effective, is testified to by the preservation of the most ancient Indian religious text, the Ṛigvéda, as redacted into a single text during the Brāhmaṃā period, without any variant readings.

THE FOUR VEDAS

The canonical division of the Védas is fourfold ( turĩya ) viz.,

1. Rigvéda ( RV )

2. Yajurveda ( YV, with the main division TS vs VS )

3. Sāmavéda ( SV )

4. Atharvavéda ( AV )

Of these, the first three were the principal original division, also called "Trayī Vidyā", that is, "the triple sacred science" of reciting hymns ( RV ), performing sacrifices ( YV ), and chanting ( SV ). This triplicity is so introduced in the Brāhmaṇās ( ShB, ABr and others ), but the Rigvéda is the older work of the three from which the other two borrow, next to their own independent Yajus, sorcery and speculative mantras.

Thus, the Mantras are properly of 3 forms :

1. Ric, which are verses of praise in metre, and intended for loud recitation;

2. Yajus, which are in prose, and intended for recitation in lower voice at sacrifices;

3. Sāman, which are in metre, and intended for singing at the Soma ceremonies.

The Yajurveda, Sāmavéda and Atharvavéda are independent collections of mantras and hymns intended as manuals for the Adhvaryu, Udgatr and Brāhmaṇ priests respectively.

The Atharvavéda is the fourth véda. Its status has occasionally been ambiguous, probably due to its use in sorcery and healing. However, it contains very old materials in early Védic language. Manusmrti, which often speaks of the three Védas, calling them trayam-Brāhma-sanātanam, "the triple eternal véda". The Atharvavéda like the Rigvéda, is a collection of original incantations, and other materials borrowing relatively little from the Rigvéda. It has no direct relation to the solemn Shrauta (Śrauta) sacrifices, except for the fact that the mostly silent Brāhmán priest observes the procedures and uses Atharvavéda mantras to 'heal' it when mistakes have been made. Its recitation also produces long life, cures diseases, or effects the ruin of enemies.

Each of the 4 Védas consists of the metrical Mantra or Saṃhitā and the prose Brāhmaṃā part, giving discussions and directions for the detail of the ceremonies at which the Mantras were to be used and explanations of the legends connected with the Mantras and rituals. Both these portions are termed shruti ( which tradition says to have been heard but not composed or written down by men ). Each of the four Védas seems to have passed to numerous Shakhas or schools, giving rise to various recensions of the text. They each have an Index or Anukramani, the principal work of this kind being the general Index or Sarvānukramaṇī.

BRAHMANAS

The mystical notions surrounding the concept of the one "véda" that would flower in védantic philosophy have their roots already in Brāhmaṃā literature, for example in the Shatapatha Brāhmaṃā. The Védas are identified with Brāhmaṇ, the universal principle ( ŚBM 10.1.1.8, 10.2.4.6 ). Vāc "speech" is called the "mother of the Védas" ( ŚBM 6.5.3.4, 10.5.5.1 ). The knowledge of the Védas is endless, compared to them, human knowledge is like mere handfuls of dirt ( TB 3.10.11.3-5 ). The universe itself was originally encapsulated in the three Védas ( ŚBM 10.4.2.22 has Prajapati reflecting that "truly, all beings are in the triple véda" ).

UPANISHADS

The Upanishads are the end part of the Vedas which briefly expound the philosophic principles of the Vedas and are considered the essence of the Vedas. The philosophy of the Upanishads is sublime, profound, lofty and soul-stirring. The Upanishads speak of the identity of the atman (individual soul) and brahman (the Supreme Soul). They reveal the most subtle and deep spiritual truths.

Overview

There is no book in the whole world that is so thrilling, soul-stirring and inspiring as the Upanishad. The philosophy taught by the Upanishads has been the source of solace for many, both in the East and the West. The human intellect has not been able to conceive of anything more noble and sublime in the history of the world than the teachings of the Upanishads.

The Upanishads contain the essence of the Vedas. They are the concluding portions of the Vedas and are the source of the Vedanta philosophy. Profound, original, lofty and sublime thoughts arise from every verse. They contain the direct spiritual experiences or revelations of seers, or sages, the rishi. They are the products of the highest wisdom, supreme divine knowledge. Hence they stir the hearts of people and inspire them.

The glory or grandeur of the Upanishads cannot be adequately described in words, because words are finite and language is imperfect. The Upanishads have indeed greatly contributed to the peace and solace of mankind. They are highly elevating and soul-stirring. Millions of aspirants have drawn inspiration and guidance from the Upanishads. They are the cream of the Vedas. They are treasures of incalculable value. They are rich in profound philosophical thought. Their intrinsic value is very great. There is immense depth of meaning in the passages and verses. The language is beautiful.

The Upanishads give a vivid description of the nature of the Atman, the Supreme Soul, in a variety of ways, and expound suitable methods and aids to attain the Immortal Brahman, the Highest Purusha.

Ages have passed since they were first presented to the world. Even now they are remarkably sweet and charming. Their freshness is unique. Their fragrance is penetrating. Many cannot live today without the study of Upanishads daily. They give supreme food for the soul.

It is said that Schopenhauer, the renowned philosopher of the West, had always a book of the Upanishads on his table, and was in the habit, before going to bed, of performing his devotions from its pages. He said,

The Upanishads have undoubtedly exercised and will continue to exercise a considerable influence on the religion and philosophy of India. They present a view of reality which would certainly satisfy the scientific, the philosophic, as well as the religious aspirations of man.

Origin Of the Upanishads

The Upanishads are metaphysical treatises which are replete with sublime conceptions of Vedanta and with intuitions of universal truths. The Indian Rishis and seers of yore endeavoured to grasp the fundamental truths of being. They tried to solve the problems of the origin, the nature and the destiny of man and of the universe. They attempted to grasp the meaning and value of knowing and being. They endeavoured to find a solution for the problems of the means of life and the world and of the relation of the individual to the ‘Unseen’ or the Supreme Soul. They sought earnestly satisfactory solution of these profound questions: Who am I? What is this universe or Samsara? When are we born? On what do we rest? Where do we go? Is there any such thing as immortality, freedom, perfection, eternal bliss, everlasting peace, Atman, Brahman, or the Self, Supreme Soul, which is birthless, deathless, changeless, self-existent? How to attain Brahman or Immortality?

They practised right living, Tapas, introspection, self-analysis, enquiry and meditation on the pure, inner Self and attained Self-Realization. Their intuitions of deep truths are subtle and direct. Their inner experiences, which are direct, first-hand, intuitive and mystical, which no science can impeach, which all philosophies declare as the ultimate goal of their endeavours, are embodied in the sublime books called the Upanishads.

The Upanishads are the knowledge portion, or Jnana-Kanda, of the Vedas. They are eternal. They came out of the mouth of Hiranyagarbha, or Brahman. They existed even before the creation of this world.

The Upanishads are a source of deep mystic divine knowledge which serves as the means of freedom from this formidable Samsara, earthly bondage. They are world-scriptures. They appeal to the lovers of religion and truth in all races, and at all times. They contain profound secrets of Vedanta, or Jnana-Yoga, and practical hints and clues which throw much light on the pathway of Self-Realization.

There are four Vedas., Rigveda, Yajurveda, Samaveda and Atharvaveda. There are as many Upanishads to each Veda as there are Sakhas or branches (subdivisions). there are 21, 109, 1000, and 50 subdivisions to Rig, Yajur, Sama, and Atharva vedas respectively. Thus there are one thousand and hundred and eighty (1,180) Upanishads.

108 Principal Upanishads

There are total 108 Upanishads according to the Muktika Upanishad. Of these, the following 12 are considered the principle Upanishads. They are:

Another 8, called minor Upanishads, are:

Significance and Ideal

Knowledge of the Upanishads destroys ignorance, the seed of Samsara. 'Shad' means to 'shatter' or 'destroy'. By having knowledge of the Upanishads one is able to sit near Brahman, i.e., to attain Self-realisation. Hence the name 'Upanishad'. Knowledge of Brahman is called 'Upanishad', because it leads to Brahman and helps aspirants to attain Brahman. The term 'Upanishad' is applied to the book also in a secondary sense, by courtesy.

The following two ideas dominate the teaching of all the Upanishads:

(1) Final emancipation can be attained only by knowledge of the Ultimate Reality, or Brahman (Brahmajnana):

(2) He who is equipped with the four means of salvation, viz., Viveka, (discrimination), Vairagya (dispassion), Shad-Sampat (the six-fold treasure; self-control, etc.) and Mumukshutva (yearning for liberation), can attain Brahman.

The Upanishads teach the philosophy of absolute unity.

The goal of men, according to the Upanishads, is realisation of Brahman. Self-Realization alone can dispel ignorance and bestow immortality, eternal bliss, and everlasting peace. Knowledge of Brahman alone can remove all sorrows, delusion and pain.

The Upanishads are rightly called the Vedanta, the end of the Vedas, that which is reserved for those who have freed themselves from the bonds of formal religion.

The Upanishads are not meant for the masses, as they contain the highest speculations of philosophy. They are meant only for the select few, who are fit and worthy to receive the instructions. Hence the term 'Upanishad' signified at first 'secret teaching' or 'secret doctrine'. As already stated, Sadhana-Chatushtaya (the fourfold means) is the primary qualification of an aspirant of Jnana-Yoga, or one who seeks the knowledge of the Upanishads.

Study the Upanishads systematically. Acquire the four means of liberation. Meditate on the non-dual Atman or Brahman and attain ever-lasting Bliss!

LIST OF 108 UPANISHADS

| from Rig Veda | from Shuklapaksha Yajurveda | from Krishnapaksha Yajurveda | from Samaveda | from Atharvaveda |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 001 Aitareya Upanishad | 011 Adhyatma Upanishad | 030 Akshi Upanishad | 062 Aruni (Aruneyi) Upanishad | 078 Annapurna Upanishad |

| 002 Aksha-Malika Upanishad - about rosary beads | 012 Advaya-Taraka Upanishad | 031 Amritabindhu Upanishad | 063 Avyakta Upanishad | 079 Atharvasikha Upanishad |

| 003 Atma-Bodha Upanishad | 013 Bhikshuka Upanishad | 032 Amritanada Upanishad | 064 Chandogya Upanishad | 080 Atharvasiras Upanishad |

| 004 Bahvricha Upanishad | 014 Brihadaranyaka Upanishad | 033 Avadhuta Upanishad | 065 Darsana Upanishad | 081 Atma Upanishad |

| 005 Kaushitaki-Brahmana Upanishad | 015 Hamsa Upanishad | 034 Brahma-Vidya Upanishad | 066 Jabali Upanishad | 082 Bhasma-Jabala Upanishad |

| 006 Mudgala Upanishad | 016 Isavasya Upanishad | 035 Brahma Upanishad | 067 Kena Upanishad | 083 Bhavana Upanishad |

| 007 Nada-Bindu Upanishad | 017 Jabala Upanishad | 036 Dakshinamurti Upanishad | 068 Kundika Upanishad | 084 Brihad-Jabala Upanishad |

| 008 Nirvana Upanishad | 018 Mandala-Brahmana Upanishad | 037 Dhyana-Bindu Upanishad | 069 Maha Upanishad | 085 Dattatreya Upanishad |

| 009 Saubhagya-Lakshmi Upanishad | 019 Mantrika Upanishad | 038 Ekakshara Upanishad | 070 Maitrayani Upanishad | 086 Devi Upanishad |

| 010 Tripura Upanishad | 020 Muktika Upanishad | 039 Garbha Upanishad | 071 Maitreya Upanishad | 087 Ganapati Upanishad |

| 021 Niralamba Upanishad | 040 Kaivalya Upanishad | 072 Rudraksha-Jabala Upanishad | 088 Garuda Upanishad | |

| 022 Paingala Upanishad | 041 Kalagni-Rudra Upanishad | 073 Sannyasa Upanishad | 089 Gopala-Tapaniya Upanishad | |

| 023 Paramahamsa Upanishad | 042 Kali-Santarana Upanishad | 074 Savitri Upanishad | 090 Hayagriva Upanishad | |

| 024 Satyayaniya Upanishad | 043 Katha Upanishad | 075 Vajrasuchika Upanishad | 091 Krishna Upanishad | |

| 025 Subala Upanishad | 044 Katharudra Upanishad | 076 Vasudeva Upanishad | 092 Maha-Vakya Upanishad | |

| 026 Tara-Sara Upanishad | 045 Kshurika Upanishad | 077 Yoga-Chudamani Upanishad | 093 Mandukya Upanishad | |

| 027 Trisikhi-Brahmana Upanishad | 046 Maha-Narayana (or) Yajniki Upanishad | 094 Mundaka Upanishad | ||

| 028 Turiyatita-Avadhuta Upanishad | 047 Pancha-Brahma Upanishad | 095 Narada-Parivrajaka Upanishad | ||

| 029 Yajnavalkya Upanishad | 048 Pranagnihotra Upanishad | 096 Nrisimha-Tapaniya Upanishad | ||

| 049 Rudra-Hridaya Upanishad | 097 Para-Brahma Upanishad | |||

| 050 Sarasvati-Rahasya Upanishad | 098 Paramahamsa-Parivrajaka Upanishad | |||

| 051 Sariraka Upanishad | 099 Pasupata Brahmana Upanishad | |||

| 052 Sarva-Sara Upanishad | 100 Prasna Upanishad | |||

| 053 Skanda Upanishad | 101 Rama Rahasya Upanishad | |||

| 054 Suka-Rahasya Upanishad | 102 Rama-Tapaniya Upanishad | |||

| 055 Svetasvatara Upanishad | 103 Sandilya Upanishad | |||

| 056 Taittiriya Upanishad | 104 Sarabha Upanishad | |||

| 057 Tejabindu Upanishad | 105 Sita Upanishad | |||

| 058 Varaha Upanishad | 106 Surya Upanishad | |||

| 059 Yoga-Kundalini Upanishad | 107 Tripadvibhuti-Mahanarayana Upanishad | |||

| 060 Yoga-Sikha Upanishad | 108 Tripura-Tapini Upanishad | |||

| 061 Yoga-Tattva Upanishad |

VEDANTA

véda Vyāsa attributed to have compiled the Védas

While contemporary traditions continued to maintain Védic ritualism ( Shrauta (Śrauta), Mimamsa ), Védāṅta renounced all ritualism and radically re-interpreted the notion of "véda" in purely philosophical terms. The association of the three Védas with the bhūr bhuvaḥ svaḥ mantra is found in the Aitareya āraṇyaka: "Bhūḥ is the Rigvéda, bhuvaḥ is the Yajurveda, svaḥ is the Sāmavéda" ( 1.3.2 ). The Upanishad or Upaniṣads reduce the "essence of the Védas" further, to the syllable Aum ( ॐ ). Thus, the Katha Upanishad or Upaniṣads has :

"The goal, which all Védas declare, which all austerities aim at, and which humans desire when they live a life of continence, I will tell you briefly it is Aum" ( 1.2.15 )

Vedānta (Devanagari: वेदान्त) a compound of veda, "knowledge" and anta, "end, conclusion", translating to "the culmination of the Vedas" — is a school of philosophy within Hinduism dealing with the nature of reality. An alternative reading is of anta as "essence", "core", or "inside", rendering the term "Vedānta" — "the essence of the Vedas". It is a principal branch of Hindu philosophy. As per some, it is a form of Jnana Yoga (one of the four basic yoga practices in Hinduism; the others are: Raja Yoga, Bhakti Yoga, Karma Yoga), a form of yoga which involves an individual seeking "the path of intellectual analysis or the discrimination of truth and reality."

Description

All forms of Vedanta are drawn primarily from the Upanishads, a set of philosophical and instructive Vedic scriptures which deal mainly with forms of meditation. "The Upanishads are commentaries on the Vedas, their putative end and essence, and thus known as Vedānta = 'End of the Veda'. They are considered the fundamental essence of all the Vedas and although they form the backbone of Vedanta, portions of Vedantic thought are also derived from some of the earlier Aranyakas.

Indian pre-Shankara Buddhist writer Bhavya in the Madhyamakahrdaya Karika describes the Vedanta philosophy as "Bhedabheda". The three branches of Vedanta best known in the West are Advaita Vedanta, Vishishtadvaita, and dvaita-advaita. Each of these Vedantic divisions was founded by Shri Adi Shankara, Shri Ramanuja and Shri Madhvacharya, respectively. Also of note, historically, in order for a guru to be considered an acharya or great teacher of a philosophical school of Vedanta, he was required to write commentaries on three important texts in Vedanta, the Upanishads, Bhagavad Gita, and the Brahma Sutras. Accordingly, Adi Sankara, Ramanuja and Shri Madhvacharya have written commentaries on all three canonical texts. The three schools they conceived are the most prevalent, however, proponents of other Vedantic schools continue to write and develop their ideas as well, although their works are not widely known outside of India.

POST-VEDIC LITERATURE

VEDANGA

The Védāṅga (Sanskrit: ""Veda-limb; member of the Veda") are six auxiliary disciplines for the understanding and tradition of the Vedas. The four Vedas form the body of the Veda Purusha or the Vedic Being. The six Védāṅgas are the limbs of the Veda Purusha. Four Vedangas govern correct chanting of the Vedas: 1) śikṣā (phonetics), 2) çhandas (meter), 3) Nirukta, "etymology", 4) Vyākaraṇa, "grammar". The two other Vedāngas are 5) Jyotisha Vedanga, "astronomy-astrology" and 6) Kalpa Vedanga, "procedural canon" which includes the Shrauta and Shulba Shastras, "ritual codes", dharma-shastra, "social law" and Grihya Shastras, "domestic codes".

Six technical subjects related to the Védas are traditionally known as Védāṅga "limbs of the véda". V. S. Apte defines this group of works as :

"N. of a certain class of works regarded as auxiliary to the Védas and designed to aid in the correct pronunciation and interpretation of the text and the right employment of the Mantras in ceremonials."

These subjects are treated in Sũtra literature dating from the end of the Védic period to Mauryan times, seeing the transition from late Védic Sanskrit to Classical Sanskrit.

The six subjects of Védāṅga are :

1) Phonetics ( śikṣā )

2) Ritual ( Kalpa )

Kalpa Vedanga or also known as the Kalpa Sutras (Sanskrit: "Procedural or ceremonial Veda-limb") - a body of three groups of auxiliary Vedic texts:

1) the Shrauta Sutras and Shulba Sutras, on public Vedic rites (yagna),

2) the Grihya Sutras (or Shastras), on domestic rites and social custom,

3) the dharma-shastra (or Sutras), on religious law.

Among all the literature related with the Vedanga, Kalpa holds a very prominent and primary place. Kalpa means the scripture, which contains the systematic imagination of all the activities as described in the Vedas. So the Kalpas are the 'precept scriptures' which systematically describe about the various religious activities and ceremonies like Yagya (oblation), marriage and sacred thread ceremony etc propounded by the Vedas. There are numerous sets of Kalpa Sutras, composed by various rishis. Each set is associated with one of the four Vedas.

Description

These aphorisms or precepts are considered as very ancient as its contents have direct relation with the 'Brahmans' and 'Aranyakas'. 'Etareya Aranyak' contains numerous statements which are in fact, in the forms of precepts or aphorisms and which are considered to have been created by 'Ashwalayan' and 'Shaunak'.

'Yagya' (oblation) was the main religious activity of the Vedic Aryans according to the traditions prevalent during the 'Brahmana period' but because of its expanse and vastness, the necessities of precise and systematic scriptures were felt for the use of the performers of the 'Yagya' (oblation).

'Kalpa Sutras' were created to meet this demand and in all the branches of the Vedas.

Kalpa Sutra is mainly of four types:-

SHRAUT SUTRA

1) SHRAUT SUTRA - it contains the description of various religious rites as mentioned in the 'Brahmans' and also the various oblations performed in the sacrificial fire.

Shrauta Shastra or Śrauta Sũtra (Sanskrit: "texts on the revelation")

a) Refers to scriptures or teachings that are in agreement with the Vedas.

b) A specific group of texts of the Kalpa Vedanga, and part of the essential study for Vedic priests.

The Shrauta Shastras offer explanation of the yagna rituals.

R̥gveda

Sāmaveda

Kr̥sna Yajurveda

Śukla Yajurveda

Atharvaveda

GRIHYA SUTRAS / GRIHYA SHASTRAS

2) GRIHYA SUTRAS or GRIHYA SHASTRAS (Sanskrit: "Household maxims or codes") - it contains the detailed description about the various oblations performed in the household like sacred thread ceremony, marriage, 'Shraadh' etc. — an important division of classical smriti literature, designating rules and customs for domestic life, including rites of passage and other home ceremonies, which are widely followed to this day. The Grihya Sutras (or Shastras) are part of the Kalpa Vedanga, "procedural maxims" (or Kalpa Sutras), which also include the Shrauta and Shulba Shastras, on public Vedic rites, and the Dharma Shastras (or Sutras), on domestic-social law. Among the best known Grihya Sutras are Ashvalayana's Grihya Sutras attached to the Rig Veda, Gobhila's Sutras of the Sama Veda, and the Sutras of Paraskara and Baudhayana of the Yajur Veda.

DHARMA SUTRA

3) DHARMA SUTRA - it contains the detailed description about the duties of all the four castes i.e. Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya and Shudra. The duties of the king are especially emphasized. It is considered as the main 'Kalpa Sutra'.

Dharma Shastra or Dharmaśāstra (Sanskrit: धर्मशास्त्र, "Religious law book.") — a term referring to all or any of numerous codes of Hindu civil and social law composed by various authors. The best known and most respected are those by Manu and Yajnavalkya. The Dharma Shastras are part of the Smriti literature, included in the Kalpa Vedanga, and are widely available today in many languages.

The Dharma Shastras, along with the Artha Shastras, are the codes of Hindu law, parallel to the Muslim Sharia, the Jewish Talmud, each of which provides guidelines for kings, ministers, judicial systems and law enforcement agencies. These spiritual-parliamentary codes differ from British and American law, which separate religion from politics. (Contemporary British law is influenced by Anglican Christian thought, just as American democracy was, and is, profoundly affected by the philosophy of its non-Christian, Deistic founders.) The Dharma Shastras also speak of much more, including creation, initiation, the stages of life, daily rites, duties of husband and wife, varnasrama, Vedic study, penances and transmigration.

Description

Written after the DharmaSũtras, these texts use a metered verse and are much more elaborate in their scope. Scholars have postulated that these texts are actually compilations of common gnomic verses of the times, known by the śiṣṭas. Such verses were regularly cited as legitimation for legal judgments and advice. At some point these verses were gathered together into complete texts under the name of particular sages. These texts are said to have been edited and updated with additions of verses which had not previously been included. However, there is an ongoing debate amongst scholars regarding this matter. Other scholars refute the multiple authorship idea, claiming that the major texts were written by a single author at a particular time in history and remained relatively unedited as time went by. Regardless, by attributing their authorship to that of well known sages like Nārada, the text takes on a superior authority. The most influential texts are listed below, along with their approximate dates:

Content

All Dharmaśāstra derives its authority with reference to the Vedas, though few, if any, of the contents of most Dharmaśāstra texts can be directly linked with extant Vedic texts. Traditionally, Dharmaśāstra has, since the time of the Yājñvalkyasmṛti, been divided into three major topics:

1) ācāra, rules pertaining to daily rituals, life-cycle rites, and other duties of four castes or varṇas,

2) vyavahāra, rules pertaining to the procedures for resolving doubts about dharma and rules of substantive law categorized according the standard eighteen titles of Hindu law,

3) prāyaŚcitta, rules about expiations and penances for violations of the rules of dharma.

SHULBA SUTRA

4) SHULBA SUTRA - it contains the methods of constructing the 'Altar' of the oblation which are based on the ancient geometrical science of the Aryans and which are considered to be very scientific.

The main subject of the Shraut Sutra is the description of the various oblations as propounded by the Vedas. The names of these Vedas are as follows:-

a) SOMYAGYA, b) VAAJAPEYA, c) RAJSUYA, d) ASHWAMEDHA etc

According to the 'Shraut Sutra' all the rituals of the oblations are performed only after igniting fire. Hence great emphasis has been given on the selection of the sacrificial fire and its re-ignition in some special circumstances. Due to their complexities the Shraut Sutras do not find any interest in the general people but their religious importance is incomparable.

Rigveda has two 'Shraut Sutras'- Ashwatayan and Shankhayan. In both of them various oblations are described which are performed by the performer with a specific purpose.

There are twelve chapters in the Ashwalayan Shraut Sutra. It is a well known fact that sage Ashwalayan was sage Shaunak's disciple and it is also believed that the last two chapters of the 'Etareya Aranyak' were the works of both of them.

Similarly the 'Shankhayan Shraut Sutra' has eighteen chapters and it has detailed description of the methods of performing the various oblations. 'Shankhayan Shraut Sutra which is related with the 'Brahmana' seems to be most ancient of all the 'Shraut Sutras' going by the contents and style of narration and it also has similarities with the 'Brahmana' to some extent. The last two chapters of its eighteen chapters are believed to be a later edition and which have similarities with the first two chapters of the 'Kaushitaki Aranyak' in its contents.

SHUKLA YAJURVEDIYA KALPASUTRA

SHUKLA YAJURVEDIYA KALPASUTRA: There are two 'precept scriptures' on the Shukla Yajurveda :

The knowledge of the contents of 'Katyayan Shraut Sutra' is essential for understanding the 'Shraut Sutra'. Katyayan Shraut Sutra is considered as a scripture representing the Shraut Sutra. Katyayan Shraut Sutra has been written in the mode of the precepts and aphorisms and is classified into 26 chapters which has a detailed description of the various types of oblations.

The first chapter of Katyayan Shraut Sutra' which consists of ten 'Kandikas' (subdivisions) describes about the characteristics of the various subjects related with oblations.

The second and third chapters which consist of eight 'Kandikas' each give the complete description of the oblations performed on the 'dark moon' and 'full moon' days. The first 'Kandika' of the second chapter gives information about the initial ceremonies and the last Kandika of the third chapter sheds light on the 'main ceremonies' or the 'main oblations'. The fourth chapter which consists of 15 'Kandikas' describe about the various oblations like 'PINDA PITRA YAGYA', 'DAKSHAYAN YAGYA', 'SHRAUT YAGYA' and 'AGNIHOTRA YAGYA' respectively.

The fifth chapter which consists of 13 Kandikas describes about the oblations and rites performed during the month of 'Chaturmasya' in great detail.

The sixth chapter which consists of 10 'Kandikas' describes about the methods of sacrificing animals.

From the seventh chapter to the tenth chapter there is a complete description of 'AGNISHTOMA YAGYA'. The seventh and eighth chapter contain the various ceremonies which are performed prior to the performance of 'AGNISHTOMA YAGYA', the ninth chapter contains the various rituals performed during the early morning and the tenth chapter describes about the various rituals performed during the noon time and during the evening time.

The eleventh chapter contains the detailed description of the works of a sacrificial priest named Brahma and the importance of his works.

Similarly the twelfth chapter contains the description about the 'DWAADASHAAHA YAGYA', the thirteenth chapter about the 'GAWAMAYAN YAGYA', the fourteenth chapter about the 'VAAJAPEYA YAGYA' and the fifteenth chapter contains the description about the 'RAAJASUYA YAGYA'.

From the sixteenth chapter to the eighteenth chapter there is a detailed description about the selection of the sacrificial fire (agnichayan).

Similarly the nineteenth chapter contains the detailed description about 'SAVTARAMANI', the twentieth chapter about the ASWAMEGHA, the twenty-first chapter about the 'PURUSHMEGHA', the 'SARVAMEGHA' and 'PITRAMEGHA YAGYA'.

The subject matters of the chapters from twenty second to twenty fourth are 'EKAHA' (oblation completed in one day), 'AHEEN' (oblation which gets completed within two to eleven days) and 'SATRA YAGYA'. The base of this section is 'TANDAYA MAHABRAHMAN' which is considered to be the main 'Brahmana' of the SAMAVEDA and hence has been appropriately adjusted in the 'SHUKLA YAJURVEDIYA BRAHMAN'.

The twenty-fifth chapter describes about the various methods of atonement for the mistakes committed during the process of oblation.

The last chapter (26th chapter) describes about 'PRAVARGYA' (classification of all the subjects).

PARASKAR GRIHYA SUTRA: The Grihya Sutra of Shukla Yajurveda is also known as Paraskar Grihya Sutra. It has been divided into three 'Kandas'.

The first 'Kanda' contains the description of 'Awasathya-Agni'. (name of a special kind of sacrificial fire) and its conception, marriage ceremony, conception of a child and 'ANNAPRASHAN' (a ceremony in which a child is given for the first time rice cooked in milk) rite which is performed on the return of the disciple to his household after finishing his studies), 'Panchamaha Yagya' (five essential duties of a householder), 'Shravanakarm' (listening to the scriptures) and Sita Yagya.

The third and the last Kanda contains the description about 'Shraadh' (act of devotion to the names) and atonement for the mistakes committed during the 'Shraadh' etc.

KRISHNA YAJURVEDA

KRISHNA YAJURVEDA: The following 'Shraut Sutras' are available which are related to 'Krishna Yajurveda'. They are:-

1. Baudhayan Shraut Sutra.

2. Apastamba Shraut Sutra.

3. Hiranyakeshi Shraut Sutra or Sanyashadha.

4. Vaikhanus Shraut Sutra.

5. Bhardwaj Shraut Sutra.

6. Manav Shraut Sutra.

The first five of these Sutras are related to the branch of 'Taitereya' and the last one is related to the branch of 'Maitrayani'. Baudhayan Shraut Sutra and Apastamba Shraut Sutra have the complete details of all the four precept scriptures (sutra grantha) of the Kalpa i.e. Shraut, Grihya Dharma and Shulva.

SAMVEDIYA KALPASUTRA

SAMVEDIYA KALPASUTRA: Among the 'Kalpa sutras' which are related with 'SAMVEDA ARSHEYA KALPA is considered to be the supreme. A sage by the name of Mashak is supposed to be the creator of this Kalpa Sutra. This enormous scripture contains eleven chapters. The main objective of this text is to show as to which 'Sama' (versus of Samaveda) is to be sung in which oblation.

There are three types of SOM YAGYA. They are as under:-

1. EKAHA:- which gets completed within a day.

2. AHEENA:- which gets completed within two days to eleven days.

3. SATRA:- which takes at least twelve days and at the most one year for completion.

Arsheya Kalpa is related to 'Tandya-Maha-Brahman' i.e. the order in which it describes about the oblations of the Samavediya Brahmana, the same order has been initiated by this Kalpa Sutra. The applications of different modes of the singing of 'Samas' (verses of Samveda) during the performance of Soma Yagya is described in detail and is the specialty of the Arsheya Kalpa.

3) Grammar ( Vyākaraṇa )

Vyākaraṇa Vedanga or Vyākaraṇa Shastra (Sanskrit: "grammar") — auxiliary Vedic texts on Sanskrit grammar. Vyakarana is among four linguistic skills taught for mastery of the Vedas and the rites of yagna. The term literally means "separation, or explanation." The most celebrated Vyakarana work is Panini's 4,000-sutra Ashtadhyayi, which set the linguistic standards for classical Sanskrit.

Words by themselves may not mean much, unless there are set rules as to their usage and more rules for their usage in combinations, forming sentences. Vyakarana performs the important function of imparting significance to Veda Vakyas. For each Shastra, there is a bhashya (just as there is the Sri Bhashya for Brahmasutras). The greatness of the Vyakarana Vedanga would be evident when we note that its bhashya is known simply as the "Maha Bhashya" (authored by Patanjali Rishi, based on the Sutras of Panini).

4) Etymology ( Nirukta )

Nirukta Vedanga (Sanskrit: "etymology Veda-limb.") — auxiliary Vedic texts which discuss the origin and development of words; among the four linguistic skills taught for mastery of the Vedas and the rites of yagna. Nirukta relies upon ancient lexicons, nighantu, as well as detailed hymn indices, anukramani. Five nighantus existed at the time of sage Yaska, whose treatise is regarded a standard work on Vedic etymology.

Description

There are altogether fourteen chapters in Nirukta out of which the first twelve chapters from the beginning are the main chapters and the two chapters in the end are given in the form of appendixes or supplementaries. These last two chapters can not be considered as a subsequent addition because sage Uvvat in his annotation of Yajurveda has taken excerpts from the Nirukta. Both he and sage ?Sayan? are well acquainted with the chapters of Nirukta. This goes to prove that the Nirukta is more ancient than the time when both these sages existed.

Nirukta is the commentary of Nighantu. In Nighantu are compiled the difficult and complex terms of the Vedas. There are difference of opinions regarding the actual numbers of Nighantu. Only one Nighantu is available nowdays. Some scholars are of the views that Nidhantu is created by none other than Yask, but followers of ancient tradition. According to the Mahabharat (Ch-342 of Moksha dharm Shlokas 86-87) sage Kashyap is the creator of Nighantu.

Therefore going by the statement made in the Mahabharat it seems that it was the creation of Prajapati Kashyap during the Mahabharat period. There are five chapters in Nighantu. The first three chapters from the beginning are called ?Naighantukand?, the fourth and the fifth chapter are called Naigam kand and Daivatkand respectively.

The first chapter contains words connected with nature and natural elements like earth. The second kand consists of root-words or mono-words.

The word Naigam means the impossibility to know about the exact meaning of the words and their nature.

In Daivat-kand is described the appearances of the deities and their abodes.

Nirukta tells us about the etymological expressions of words & its derivations. The meaning varies according to the etymological expressions.

Important of the Nirukta

The important of the Nirukta created by Yask is very great. In the very beginning of his literary composition sage Yask has illustrated about the principle of Nirukta in a scientific way. During his time the meanings of Vedas were interpreted on the basis of diverse opinions, which were as follows.

1. Adhidaivat

2. Adhyatm

3. Aakhyan Samay

4. Ethihasikah

5. Naidanah

6. Nairuktah

7. Parivrajahah

8. Yagyikah

These above mentioned various opinions shed light on the history of different contemplation?s of the Vedas.

Sage Yask had a great impact on many commentators of the Vedas in due course of time. Sage Sayan accomplished his commentaries of the Vedas after contemplating on his very system. Yask's processes are also accepted and followed by the linguists of modern age. Being the sole representative of the Nirukta, the importance of Yasks volume is great.

Although Nirukta is itself is a commentary of the Vedas, but still, it is so complex at certain places that even the most learned commentators fail to understand its real meaning. Moreover the exact chapter of Nirukta are nor available traditionally. Along with the difficult language which the Nirukta contains its chapters are so complex at certain places that even a great annotator like Durgacharya experienced difficulty in understanding it. Because of its complex nature many scholars, before Vikram have tried their hands at writing commentaries on it.

Commentators of Nirukta

1) DURGACHARYA: Durgacharya is one of the most ancient commentator of the Nirukta, but he is certainly not the first one to do so. Numerous commentaries of earlier annotators are mentioned in his volume.

2) SKAND MAHESHWAR: This commentary is very ancient and scholarly. Commentary on the Rigveda is also available.

Importance of Nirukta

The term "Nirukta" has been described by sage Sayanacharya in the following way

"ARTHAVABODHE NIRPEKSHATAYA PADJATAM YATRA TAT NIRUKTAM"

The collection of independent words which helps in understanding their meaning are called Nirukta.

Durgacharya is of the opinion that Nirukta is supreme among the Vedanga and volumes because it helps us to understand the meaning of the words. The meaning of the word is of primary importance and the word itself is of secondary importance. Grammar is nothing but the study of the words. In ?Kalps? (part of Veda treating of rituals) the proper use of the Mantras in the vedic ceremonies are described. The mantra is used only in such situation where the words contained in that mantra is capable of expressing themselves completely. Therefore Kalpa too helps in gaining knowledge of mantras meaning.

Nirukta is of greater value than Kalpa because it helps in understanding the meanings of words, in all of their probable permutations and combinations, where as Kalpa helps to understand the meanings of mantras, which themselves consist of words.

Although the study of grammar also helps in understanding the characteristics of words but I can not interpret the meaning of words as deeply as Nirukta. Therefore the study of the Nirukta is very necessary to understand the Vedas. It is a supplementary science of Grammar.

5) Meter ( Çhandas )

Çhandas Vedanga (Sanskrit: "meter") - auxiliary Vedic texts on the metrical rules of poetic writing. çhanda is among four linguistic skills taught for mastery of the Vedas and the rites of yagna. çhandas means "desire; will; metrical science." The most important text on çhandas is the Çhanda Shastra, ascribed to Pingala. Its knowledge is most essential for the correct pronunciation of the Vedic mantras.

Just as the knowledge of the internal system of the human-body is most essential for a physician, in the similar way the knowledge of çhand is most essential for a 'Vaidic' (one who studies the Veda). Without its appropriate knowledge the mantras of Vedas can never be correctly pronounced. The knowledge of deity, sage, and çhand is very essential for each Sukta (Vedic text, collection of mantras) of the Veda. Sage Katyayan has clearly stated that, one who studies or chants the mantras; or teaches them to others; or performs oblation without having the appropriate knowledge of its çhand, 'Sage' and the deity, all of his objectives remain unfulfilled.

DescriptionThe names of the main çhand are available in the Sanhita and the Brahmanas. This goes to prove that, this organ i.e. çhand already existed even during the Vedic period. Chand Sutra is the representative volume of this 'Organ' of the Veda, created by Sage Pingalacharya. This volume is written in the form of precept and is classified into eight chapters. From the beginning and till the seventh 'Sutra' (precept) of the fourth chapter, the characteristics of Vaidic Çhand are described. After that there are descriptions of general Chand (Laukik Chhand).

The binding of stanzas are meters in the Laukik Chhand are not as strict in its prose form, as it in its. Verse form. But in the 'Vaidic-Chhand' the purity of the stanzas and meters are strictly applied. In the Nirukta it has been stated that-

"NACHCHHANDAI VAGUCHCHARIT"

Without the Chhand (stanza), one ca not even pronounce.

Even Sage Bharat has declared that there is no existence of word without the stanza (Chhand).

Katyayan has accepted the above mentioned fact-

CHHANDOBHUTMIDAM SARVAM VANGMAY SYAT VIJANATAH|

NACHCHHAND NA CHAPRISHTE SHABDASHCHARATIKASHCHAN||All the saying of this whole world are bound by the 'Chhand'. There is no word, which is different from it.

The above statements clearly show that not a single mantra of the Veda is created without the Chhand. Therefore, it can be said that even the mantras of the Yajurveda, which has been written in prose form, are not devoid of the 'Chhand'. The ancient preceptors have classified 'Chhandas' consisting of one letter to one hundred and four letters.

All the mantras of Rigveda and Samveda, which are also known as 'Richas', are written in the form of stanzas.

Chhand is the natural medium to express the finer emotions of the heart. The poets try to find the body for the soul (poetry) by the help of Chhand. The chief objective of the mantra if to please the deity, during the oblation. The chanting of the mantras are undoubtedly the chief medium of pleasing the deities. In this regard, the importance of Chhand is obvious.

According to Yask, the term Chhand is derived from the root 'Chhand' which means to cover up. So, Chhand are the coverings by which the Vedas remain covered.

One of the main characteristics of the Vaidic Chhand are that normally all of them are based on the calculation of letters or alphabets. This implies that they do not follow the rule of 'sequence of the major or minor form of the letters'.

According to the scriptures there are two types of Chhand-

1. Varnik Chhand (alphabetical stanzas)

2. Matrik Chhand (stanzas containing short vowels)

In the Vedas, we normally find the former type of Chhand. The descriptions of Chhand of each 'Samhita' are minutely described in the contexts of 'Pratishakhya'. Katyayan has authentically instructed about the Chhand of each mantra of Rigveda in 'Sarvanukramam'.

'Chhand' has been extensively described in Pratishakhya, especially Rik-Pratishakhya (Patal 16-18) similarly it also contains described of other Vaidic Chhands.

6) Astronomy ( Jyotiṣa )

Jyotisha Vedanga (Sanskrit: "Veda-limb of celestial science or astronomy-astrology") - ancient texts giving knowledge of astronomy and astrology, for understanding the cosmos and determining proper timing for Vedic rites.

PARISISTA

Pariśiṣṭa "supplement, appendix" is the term applied to various ancillary works of Védic literature, dealing mainly with details of ritual and elaborations of the texts logically and chronologically prior to them: the Saṃhitās, Brāhmaṇās, Āraṇyakas and Sũtras. Naturally classified with the véda to which each pertains, Pariśiṣṭa works exist for each of the 4 Védas. However, only the literature associated with the Atharvavéda is extensive.

PURANAS

A traditional view given in the Vishnu Purana ( likely dating to the Gupta period ) attributes the current arrangement of 4 Védas to the mythical sage véda Vyāsa. Puranic tradition also postulates a single original véda that, in varying accounts, was divided into 3 or 4 parts. According to the Vishnu Purana ( 3.2.18, 3.3.4 etc. ) the original véda was divided into 4 parts, and further fragmented into numerous shakhas, by Lord Vishnu in the form of Vyāsa, in the Dvapara Yuga; the Vayu Purana ( section 60 ) recounts a similar division by Vyāsa, at the urging of Brāhma. The Bhagavata Purana ( 12.6.37 ) traces the origin of the primeval véda to the syllable aum, and says that it was divided into 4 at the start of Dvapara Yuga, because men had declined in age, virtue and understanding. In a differing account Bhagavata Purana ( 9.14.43 ) attributes the division of the primeval véda ( aum ) into 3 parts to the monarch Pururavas at the beginning of Treta Yuga. The Mahābhārata ( santiparva 13,088 ) also mentions the division of the véda into 3 in Treta Yuga.

Purana (Sanskrit: पुराण purāṇa, meaning "belonging to ancient or olden times") is the name of an ancient Indian genre (or a group of related genres) of Hindu literature (as distinct from oral tradition). Its general themes are history, tradition and religion. While the major puranas are in Sanskrit, puranas exist in other Indian languages also. It is usually written in the form of stories related by one person to another.

Overview

There are many texts designated as 'Purana.' The most important are:

According to tradition, the Puranas were composed by Vyasa at the end of Dvapara Yuga.

The Darsanas are very stiff. They are meant only for the learned few. The Puranas are meant for the masses with inferior intellect. Religion is taught in a very easy and interesting way through these Puranas. Even to this day, the Puranas are popular. The Puranas contain the history of remote times. They also give a description of the regions of the universe not visible to the ordinary physical eye. They are very interesting to read and are full of information of all kinds. Children hear the stories from their grandmothers, Pandits and Purohits (priests) hold Kathas in temples, on banks of rivers and in other important places. Agriculturalists, labourers and bazaar people (common masses) hear the stories.

Mahāpurāṇas and Upapurāṇas

Mahāpurāṇas and Upapurāṇas, the main Puranic corpus Mahapuranas are deemed to be the upper corpus of Puranas.

Traditionally there are 18 Maha-puranas. Each Maha-purana lists eighteen canonical puranas, but the contents of each list vary reflecting differences in time and place. These eighteen maha-puranas are divided into three groups and each group has six texts.

The Mahapuranas is a description of the Hindu trinity lords namely, Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. Since all three are important gods, all these are given due emphasis in any Purana. But the relative emphasis often varies from Purana to Purana.

Classification of Maha-puranas:

Vaishnava classification by guna

Of the Mahapuranas it is said that six belong to the quality (guna) of goodness, six to passion, and six to ignorance. According to the Padma Purana, these are the Mahapuranas and their corresponding qualities:

The author of Mahapuranas

The Puranas were composed by sage vyasa - the narrator of Mahabharata. The texts, the scholars say, were probably written all over India and are being rewritten and reedited to the present day all over the world.

The term purana, which means "belonging to ancient times" or "an ancient tale or legend," appears in the Vedas. The specific corpus of the Mahapuranas, as opposed to generic purana "ancient tale", are generally estimated to date to the Early Middle Ages, or to roughly between the 5th and 10th centuries, but may contain older material.

Puranic genealogies

The Puranas also lay emphasis on keeping a record of genealogies. Vayu Purana once stated that, "As seen by good people in the ancient times the suta's duty was to preserve the genealogies of gods and glorious kings and the traditions of great men". The Puranic genealogies add up to fantastic time depths. The Vedic and Puranic genealogies indicate a greater antiquity of the Vedic culture.

The Five Characteristics of purāṇas

The Puranas are of the same class as the Itihasas and are classified into a Mahā- ("great") and a Upa- ("lower, additional") corpus. According to Matysa Purana, they are said to narrate and deal systematically with five subjects, called Pancha Lakshana pañcalakṣaṇa ("five distinguishing marks"):

Most Mahapuranas and Upapuranas deal with these subject matters, although the bulk of their text consists of historical and religious narratives. A Purana usually gives prominence to a certain deity (Shiva, Vishnu or Krishna, Durga). Most use an abundance of religious and philosophical concepts in their narration, from Bhakti to Samkhya.

The Eighteen Upa-Puranas

There are eighteen main Puranas and an equal number of subsidiary Puranas or Upa-Puranas. The main Puranas are:

Of these, six are Sattvic Puranas and glorify Vishnu; Six are Rajasic Puranas and glorify Brahma; six are Tamasic Puranas and glorify Siva.

Neophytes or beginners in the spiritual path are puzzled when they go through Siva Purana and Vishnu Purana. In Siva Purana, Lord Siva is highly eulogised and an inferior position is given to Lord Vishnu. Sometimes Vishnu is belittled. In Vishnu Purana, Lord Hari (Vishnu) is highly eulogised and the inferior status is given to Lord Siva. Sometimes Lord Siva is belittled. This is only to increase the faith of the devotees in their particular Ishta-Devata (favourite or tutelary deity). Lord Siva and Lord Vishnu are one.

The best among the Puranas are the Srimad Bhagavata and the Vishnu Purana. The most popular is the Srimad Bhagavata Purana. Next comes Vishnu Purana. A portion of the Markandeya Purana is well known to all Hindus as Chandi, or Devimahatmya. Worship of God as the Divine Mother is its theme. Chandi is read widely by the Hindus on sacred days and Navaratri (Durga Puja) days.

Other Puranas

Besides the two major types of puranas namely the Maha-puranas and Upa-puranas, there are other two Hindu puranas namely, Sthala puranas, Kula puranas and others.

Sthala puranas: These texts narrates the virtues and stories connected with a certain temple or shrine (the word 'Sthala' means 'Place' in Sanskrit). There are numerous Sthala Puranas, most written in vernaculars, some with Sanskrit versions as well. Most claim to have a Sanskrit origin, and some of the Sanskrit versions also appear in a Mahapurana or an Upapurana.

Kula puranas: These puranas are caste or family oriented. They deal with a caste's origin myth, stories and legends. The kula puranas is of uttermost importance as it is an important source for caste identity and is usually contested by other, rival, castes. This subgenre is usually in the vernacular language and might at times be oral.

Other puranas: There are many other narratives that go by the name of Purana. Most are written in vernaculars and are usually concerned with mythical and historical narrations. These texts, such as the Padma Purana of Bengal and Assam (narrating the story of the goddess Manasa), are vast in number and scattered all over the Indian subcontinent.

Utility of the Puranas

Study of the Puranas, listening to sacred recitals of scriptures, describing and expounding of the transcendent Lilas (divine sports) of the Blessed Lord – these form an important part of Sadhana (spiritual practice) of the Lord's devotee. It is most pleasing to the Lord. Sravana (hearing of the Srutis or scriptures) is a part of Navavidha-Bhakti (nine modes of devotion). Kathas (narrative or story) and Upanyasas open the springs of devotion in the hearts of hearers and develop Prema-Bhakti (divine love for God) which confers immortality on the Jiva (individual soul).

[Note: The nine modes of devotion are: Hearing His (God's) names and glories, singing them, remembering the Lord, worship (service) of His Feet, adoration with flowers, prostrations, regarding oneself as His servant, as His friend, and total self-surrender.]

The language of the Vedas is archaic, and the subtle philosophy of the Vedanta and the Upanishads is difficult to grasp and assimilate. Hence, the Puranas are of special value as they present philosophical truths and precious teachings in an easier manner. They give ready access to the mysteries of life and the key to bliss. Imbibe their teachings. Start a new life of Dharma-Nishtha and Adhyatmic Sadhana from this very day.

[Note; Dharma-Nishtha = steadfastness or establishment in Dharma. Adhyatmic (pertaining to the Inner Self) Sadhana (spiritual practice)]

Translations

The Puranas are available in vernacular translations and are disseminated by Brahminscholars, who read from them and tell their stories, usually in Katha sessions (in which a travelling brahmin settles for a few weeks in a temple and narrates parts of a Purana, usually with a bhakti perspective).

The Tamil Puranas

Lord Siva incarnated Himself in the form of Dakshinamurti to impart knowledge to the four Kumaras. He took human form to initiate Sambandhar, Manikkavasagar and Pattinathar. He appeared in flesh and blood to help his devotees and relieve their sufferings. The divine Lilas (sports) of Lord Siva are recorded in the Tamil Puranas like Siva Purana, Periya Purana, Siva Parakramam and Tiruvilayadal Purana.

UPAVEDA

The term Upavéda ( "applied knowledge" ) is used in traditional literature to designate the subjects of certain technical works. Lists of what subjects are included in this class differ among sources. The Charanavyuha mentions four UpaVédas:

But Sushruta and Bhavaprakasha mention Áyurveédic as an Upavéda of the Atharvavéda. Sthapatyavéda ( architecture ), Shilpa Śāstras ( arts and crafts ) are mentioned as fourth Upavéda according to later sources.

"FIFTH" AND OTHER VEDAS

Some post-Védic texts, including the Mahābhārata, the Natyaśāstra and certain Puranas, refer to themselves as the "fifth véda". The earliest reference to such a "fifth véda" is found in the Chandogya Upanishad or Upaniṣads. "Dravida véda" is a term for canonical Tamil Bhakti texts.

Other texts such as the Bhagavad Gita or the Védāṅta Sũtras are considered shruti or "Védic" by some Hindu denominations but not universally within Hinduism. The Bhakti movement, and Gaudiya Vaishnavism in particular extended the term véda to include the Sanskrit Epics and Vaishnavite devotional texts such as the Pancaratra.

WESTERN INDOLOGY

The study of Sanskrit in the West began in the 17th century. In the early 19th century, Arthur Schopenhauer drew attention to Védic texts, specifically the Upanishad or Upaniṣads. The importance of Védic Sanskrit for Indo-European studies was also recognized in the early 19th century. English translations of the Saṃhitās were published in the later 19th century, in the Sacred Books of the East series edited by Müller between 1879 and 1910. Ralph T. H. Griffith also presented English translations of the four Saṃhitās, published 1889 to 1899.

BACK TO PAGE

Notes

READ MORE

English pronunciation : véda / Vētā / Vētam / Vēdham āyvukaḷ / ñāṉam Vaḷarcci Peṟa / Rikvēdaṁ / Rik vētam / Yajūr vētam / Sāma vētam / Atarvaṉa vētam /

Sanskrit संस्कृतम् : वेद /

Tamil தமிழ் : வேதா / வேதம் ஆய்வுகள் / ஞானம் வளர்ச்சி பெற / ரிக் வேதம் / யஜூர் வேதம் / சாம வேதம் / அதர்வன வேதம்

Bahasa Melayu : Rigvéda / Yajurveda / Sāmavéda / Atharvavéda /

Malayalam : not_available /

Telugu : రుగ్వేదం ( Rugvēdaṁ ) / యజుర్వేదం ( Yajurvēdaṁ) / సామవేదం ( Sāmavēdaṁ ) / అధర్వ వేదం ( Adharva vēdaṁ ) /

Français : not_available

Introduction

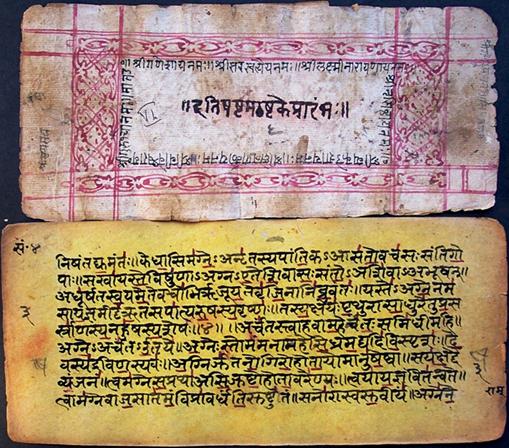

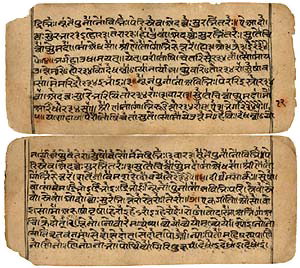

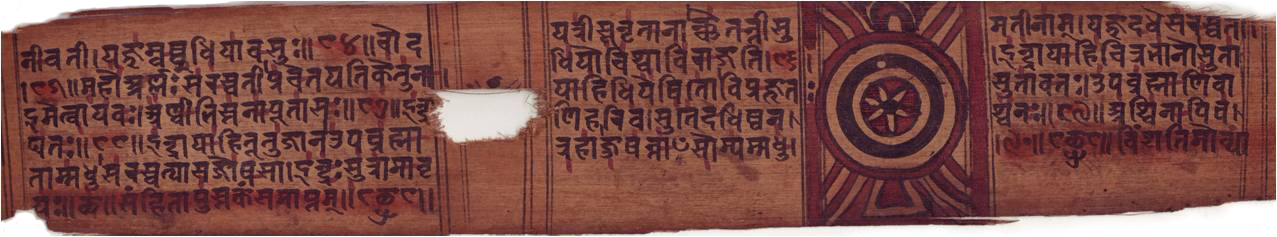

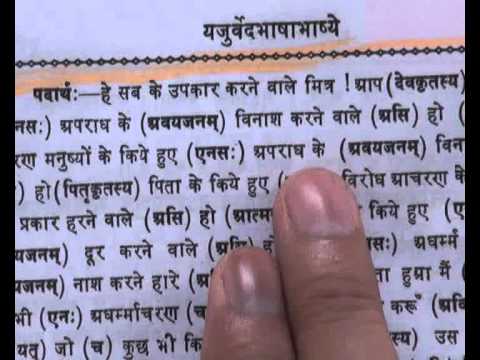

Rigvéda ( padapatha ) manuscript in Devanagari, early 19th century

Rigvéda collection of Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Pune

The Rigvéda ( Sanskrit : ऋग्वेद ṛgvéda, a compound of ṛc "praise, verse" and véda "knowledge" ) is an ancient Indian sacred collection of Védic Sanskrit hymns. It is counted among the four canonical sacred texts ( Śruti ) of Hinduism known as the Védas. Some of its verses are still recited as Hindu prayers, at religious functions and other occasions, putting these among the world's oldest religious texts in continued use. The Rigvéda contains several mythological and poetical accounts of the origin of the world, hymns praising the gods, and ancient prayers for life, prosperity, etc.

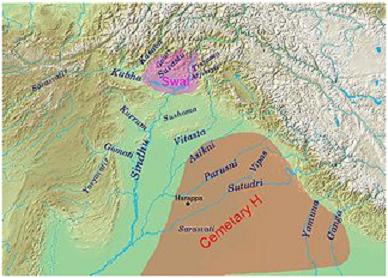

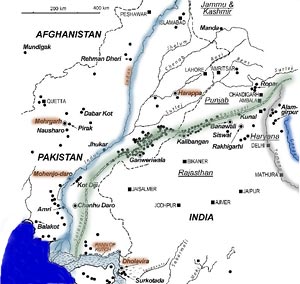

It is one of the oldest extant texts in any Indo-European language. Philological and linguistic evidence indicate that the Rigvéda was composed in the north-western region of the Indian subcontinent, roughly between 1700–1100 BC ( the early Védic period ).

The Rigvéda Saṃhitā is the oldest extant Indic text. It is a collection of 1,028 Védic Sanskrit hymns and 10,600 verses in all, organized into ten books ( Sanskrit : mandalas ). The hymns are dedicated to Rigvédic deities.

The books were composed by poets from different priestly groups over a period of several centuries, commonly dated to the period of roughly the second half of the 2nd millennium BCE ( the early Védic period ) in the Punjab ( Sapta Sindhu ) region of the Indian subcontinent.

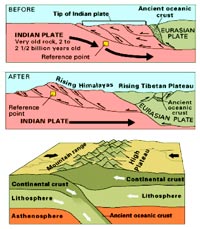

There are strong linguistic and cultural similarities between the Rigvéda and the early Iranian Avesta, deriving from the Proto-Indo-Iranian times, often associated with the Andronovo culture; the earliest horse-drawn chariots were found at Andronovo sites in the Sintashta-Petrovka cultural area near the Ural Mountains and date to ca. 2000 BCE.

Text

The surviving form of the Rigvéda is based on an early Iron Age ( c. 10th c. BC ) collection that established the core 'family books' ( mandalas 2-7, ordered by author, deity and meter ) and a later redaction, co-eval with the redaction of the other Védas, dating several centuries after the hymns were composed. This redaction also included some additions ( contradicting the strict ordering scheme ) and orthoepic changes to the Védic Sanskrit such as the regularization of sandhi ( termed orthoepische Diaskeuase by Oldenberg, 1888 ).

As with the other Védas, the redacted text has been handed down in several versions, most importantly the Padapatha that has each word isolated in pausa form and is used for just one way of memorization; and the Saṃhitāpatha that combines words according to the rules of sandhi ( the process being described in the Pratisakhya ) and is the memorized text used for recitation.

The Padapatha and the Pratisakhya anchor the text's fidelity and meaning and the fixed text was preserved with unparalleled fidelity for more than a millennium by oral tradition alone. In order to achieve this the oral tradition prescribed very structured enunciation, involving breaking down the Sanskrit compounds into stems and inflections, as well as certain permutations. This interplay with sounds gave rise to a scholarly tradition of morphology and phonetics. The Rigvéda was probably not written down until the Gupta period ( 4th to 6th century AD ), by which time the Brāhmi script had become widespread ( the oldest surviving manuscripts date to the Late Middle Ages ). The oral tradition still continued into recent times.

The original text ( as authored by the Rishis ) is close to but not identical to the extant Saṃhitāpatha, but metrical and other observations allow to reconstruct ( in part at least ) the original text from the extant one, as printed in the Harvard Oriental Series, vol. 50 ( 1994 ).

Organisation

The text is organized in 10 books, known as Mandalas, of varying age and length. The "family books": mandalas 2–7, are the oldest part of the Rigvéda and the shortest books; they are arranged by length and account for 38% of the text. The eighth and ninth mandalas, comprising hymns of mixed age, account for 15% and 9%, respectively. The first and the tenth mandalas are the youngest; they are also the longest books, of 191 Sūktas each, accounting for 37% of the text.

Each mandala consists of hymns called sūkta ( su-ukta, literally, "well recited, eulogy" ) intended for various sacrificial rituals. The sūktas in turn consist of individual stanzas called ṛc ( "praise", pl. ṛcas ), which are further analysed into units of verse called pada ( "foot" ). The meters most used in the ṛcas are the jagati ( a pada consists of 12 syllables ), trishtubh ( 11 ), viraj ( 10 ), gayatri and anushtubh ( 8 ).

For pedagogical convenience, each mandala is synthetically divided into roughly equal sections of several sūktas, called anuvāka ( "recitation" ), which modern publishers often omit. Another scheme divides the entire text over the 10 mandalas into aṣṭaka ( "eighth" ), adhyāya ( "chapter" ) and varga ( "class" ). Some publishers give both classifications in a single edition.

The most common numbering scheme is by book, hymn and stanza ( and pada a, b, c..., if required ). E.g., the first pada is

Recensions

The major Rigvédic shakha ( "branch", i. e. recension ) that has survived is that of Śākalya. Another shakha that may have survived is the Bāṣkala, although this is uncertain. The surviving padapatha version of the Rigvéda text is ascribed to Śākalya. The Śākala recension has 1,017 regular hymns, and an appendix of 11 vālakhilya hymns which are now customarily included in the 8th mandala ( as 8.49–8.59 ), for a total of 1028 hymns. The Bāṣkala recension includes 8 of these vālakhilya hymns among its regular hymns, making a total of 1025 regular hymns for this Śākhā. In addition, the Bāṣkala recension has its own appendix of 98 hymns, the Khilani.

In the 1877 edition of Aufrecht, the 1028 hymns of the Rigvéda contain a total of 10,552 ṛcs, or 39,831 padas. The Shatapatha Brāhmaṃā gives the number of syllables to be 432,000, while the metrical text of van Nooten and Holland ( 1994 ) has a total of 395,563 syllables ( or an average of 9.93 syllables per pada ); counting the number of syllables is not straightforward because of issues with sandhi and the post-Rigvédic pronunciation of syllables like súvar as svàr.

Rishis

Tradition associates a rishi ( the composer ) with each ṛc of the Rigvéda. Most sūktas are attributed to single composers. The "family books" ( 2 - 7 ) are so-called because they have hymns by members of the same clan in each book; but other clans are also represented in the Rigvéda. In all, 10 families of rishis account for more than 95% of the ṛcs; for each of them the Rigvéda includes a lineage-specific āprī hymn ( a special sūkta of rigidly formulaic structure, used for animal sacrifice in the soma ritual ).

| Family | āprī | ṛcas |

|---|---|---|

| Angiras | I.142 | 3619 ( especially Mandala 6 ) |

| Kanva | I.13 | 1315 ( especially Mandala 8 ) |

| Vasishtha | VII.2 | 1276 ( Mandala 7 ) |

| Vishvamitra | III.4 | 983 ( Mandala 3 ) |

| Atri | V.5 | 885 ( Mandala 5 ) |

| Bhrgu | X.110 | 473 |

| Kashyapa | IX.5 | 415 ( part of Mandala 9 ) |

| Grtsamada | II.3 | 401 ( Mandala 2 ) |

| Agastya | I.188 | 316 |

| bhārata | X.70 | 170 |

Manuscripts

There are, for example, 30 manuscripts of Rigvéda at the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, collected in the 19th century by Georg Bühler, Franz Kielhorn and others, originating from different parts of India, including Kashmir, Gujarat, the then Rajaputana, Central Provinces etc. They were transferred to Deccan College, Pune, in the late 19th century. They are in the Sharada (Śāradā) and Devanagari scripts, written on birch bark and paper. The oldest of them is dated to 1464. The 30 manuscripts of Rigvéda preserved at the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Pune were added to UNESCO's "Memory of the World Register in 2007.

Of these 30 manuscripts, 9 contain the Saṃhitā text, 5 have the padapatha in addition. 13 contain Sayana's commentary. At least 5 manuscripts ( MS. no. 1/A1879-80, 1/A1881-82, 331/1883-84 and 5/ViŚ I ) have preserved the complete text of the Rigvéda. MS no. 5/1875-76, written on birch bark in bold Sharada (Śāradā), was only in part used by Max Müller for his edition of the Rigvéda with Sayana's commentary.

Müller used 24 manuscripts then available to him in Europe, while the Pune Edition used over five dozen manuscripts, but the editors of Pune Edition could not procure many manuscripts used by Müller and by the Bombay Edition, as well as from some other sources; hence the total number of extant manuscripts known then must surpass perhaps 80 at least.

Contents